In Alchemy class a few weeks ago, we watched Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris and then put the question "Is Hari human?" up for debate. After immersing myself in Tarkovsky’s psychological dreamscape that so effortlessly diffuses the perceived binary between natural and artificial, real and unreal, and (most of all) human and non-human, I haven't been able to get the question out of my mind ever since. Because what does "human" even mean?

Science doesn't seem to have an answer for us. Some paleoanthropologists equate human with the species Homo sapiens, others with the whole genus Homo; some restrict it to the subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, and still others identify it with the entire hominini lineage. These disagreements aren't for a lack of evidence, but for a lack of a consensus about what sort of evidence can definitively prove which group(s) of primates should be considered human. Scientists aren’t equipped to tell us whether an organism is a human organism because “human” is a folk category rather a scientific one. Thus the question falls to cultural critique and philosophy, and philosophers have tried to answer it across the centuries and continue to try to this day.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines "human" as "being, relating to, or belonging to a person or to people as opposed to animals; having the qualities, faults, and feelings that people have, as opposed to gods, animals, or machines". The etymology sends us to the Latin root homo, loosely denoting things "of man" or "of men".

Some, like psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, think that it's language that sets us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom, or in his words, "man is the animal who speaks."

Some, like Heidegger, see being human, what he calls dasein, as the highest position in a hierarchy of wealth in worlds. To Heidegger, a thing is worldless, an animal is poor in world, but dasein (literally a human being) is rich in world.

To his student and lover, Hannah Arendt, humans are the only creatures that "can express otherness and individuality, [who] can distinguish and communicate himself and not merely some affect—thirst or hunger, affection or hostility, or fear," (The Freedom to be Free 25).

And still some, like Hari in Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris, think that being human is determined by our ability to feel, to love and be loved, and to remain human in inhuman conditions. To Hari, as perhaps to Tarkovsky, to be human is to be humane, and to be humane is to remain faithful to a moral disposition.

Today, in the 21st century, at this technological precipice in history, where the worlds that we are "rich in" are created by corporations and fed to us through our screens, where language models are writing faster than we are, and where more of us search for numbing agents to calm us in the midst of world crisis, it feels like an appropriate time to reflect on what it means to be human.

We know that this question must have been on Tarkovsky's mind while making this film given that, throughout, he offers us multiple opportunities to reflect on and evaluate our understanding of our own humanity.

Central to the film's experience is a progression of polar tensions, beginning at Kris' father's house on earth, between the garden and the city, the present and the past, the earthly, human scientists and the alien planet Solaris, the scientific, progressive "Kris" and his traditional, innovation-hating father. And while these poles are presented as distinct in the opening sequences of the film, after Kris' departure to the space station, things begin to become more and more ambiguous, the polarities inch closer and closer together, and the boundary around what it means to be human, organic, or real begins to dissolve.

By the end of the film we're left only with questions. What was real and what was illusion? Was Kris ever on earth to begin with? Did the entire film take place in an imaginary realm? Was Hari human or was she, and everything else, merely a creation of Solaris?

Well, first of all, for those of us who haven't seen the film—who is Hari?

WHO IS HARI? A SUMMARY

Hari is both Kris' dead ex-wife on earth and a simulation of Kris' memory of his dead ex-wife created by Solaris and placed on the space station orbiting it.

[what?!]

Ok let's take it back.

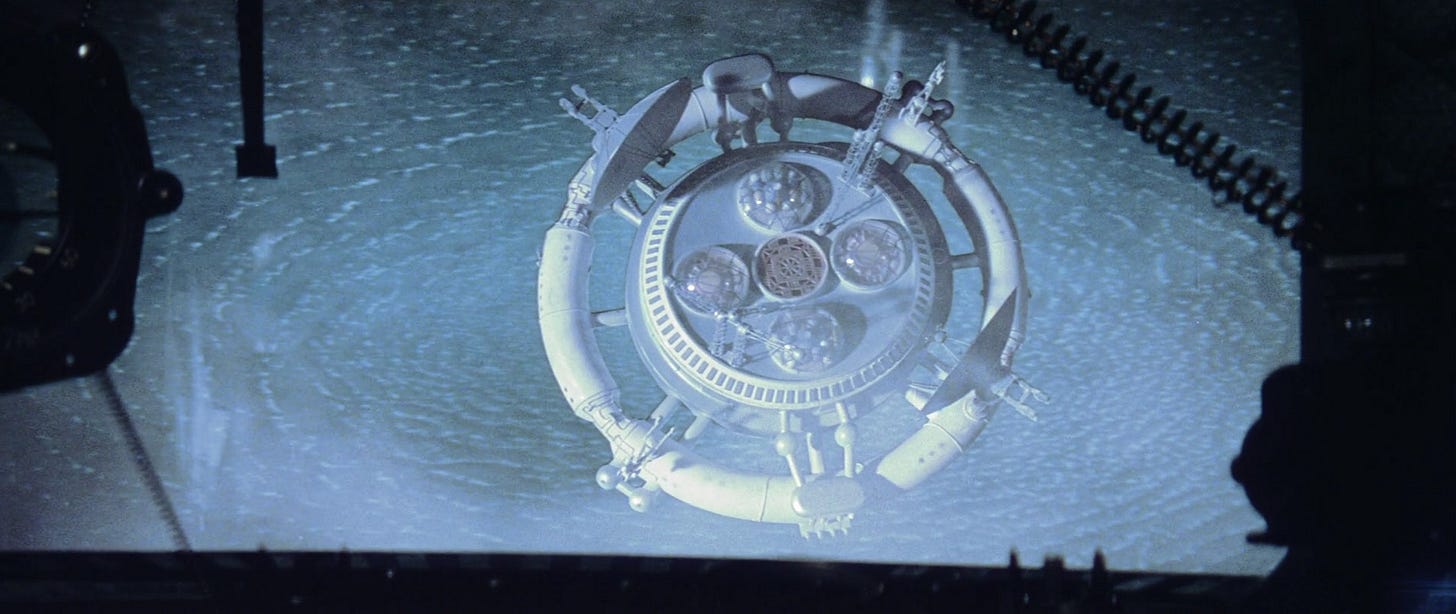

Solaris is a 1972 science-fiction film about the psychologist, Kris Kelvin, who is sent to a space station orbiting the planet Solaris to study the planet's behavior because something strange has been happening. Solaris' ocean appears to be a cognizant being, tapping into the minds of the humans orbiting it, and sending them "visitors" in the forms of people from their memories.

When Kris arrives at the space station, he learns that the only scientist he knew of the three on-board, Gibarian, has killed himself. Kris learns this when he finds the suicide tapes Gibarian has left him, where he ominously describes his own experience with Solaris and what he calls "the visitors", warning Kris not to think he'd lost his mind if he saw them. Soon after, the planet sends a visitor for Kris: his late wife Hari. Though Kris tries to get rid of her, she regenerates, with what appears to be more self-awareness and memory of her time on the station.

The other scientists, Snaut and Sartorius, inform Kris that Hari is a form sent by the planet Solaris, and is made of something called "neutrinos" rather than atoms, an unstable material held together by the planet Solaris capable of eternal regeneration, making her virtually indestructible except through the use of a device developed by Sartorius called "The Annihilator". Snaut informs Kris that the appearances of these visitors began after the scientists conducted radiation experiments on the planet's surface in an attempt to understand it, and warns him not to mistake them for real people.

Nonetheless, Kris becomes more and more absolved by Hari's presence, and is forced to contend with his grief, guilt, and other unexamined emotions around his wife's death, while Hari becomes more and more independent, develops more and more awareness of her existence, and asserts time and again that she is not Hari. As the film progresses, she becomes capable of existing away from Kelvin's presence, acquires a sense of curiosity, and eventually makes the decision to sacrifice herself for Kelvin's well-being.

After Hari's sacrifice, we learn that Snaut has broadcast Kelvin's brainwaves onto the planet and the visitors have stopped—instead, the planet has started to produce islands on its surface. In the closing scene of the film, we see Kelvin kneeling before his father at his front door step. He appears to have returned to earth, to his father's home, where the film began, but as he and his father embrace, the camera slowly cranes away to reveal that they aren't on earth at all, but are in fact on an island on Solaris.

HUMANITY, LOVE, AND THE TARKOVSKIAN IDEAL

“In all that I have done, in all that I intend to do…my theme is this: a man gripped by an ideal, searches passionately for the answer to a question, goes to the limit in his attempt to understand reality. And he obtains this understanding, thanks to his strivings, to his experience”

(Tarkovsky, quoted in Hyman 57).

More often than not, Tarkovsky's characters are to search for their "ideal" in the harshest of conditions. In Andrei Rublev, for example, the artist searches for freedom in art amidst the corruption of a war-torn, medieval Russia. In Stalker, the protagonists must journey through spaces that defy the laws of physics to reach their desires. And in Solaris, Kris Kelvin has to find a way to communicate with an alien planet while it presents itself to him as the distracting and distressing image of his dead ex-wife, his grief over whom, it quickly becomes apparent, is still largely unresolved. The question that Kris is apparently trying to answer is whether or not Hari can be loved enough to become human.

Tarkovsky, an Orthodox Christian man who lived and worked in the Soviet Union for most of his life, was interested in creating moral characters who struggle through harsh conditions that give them the opportunity to demonstrate their morality through love, sacrifice, memory, and how they choose to respond to certain situations. Kevin's moral character, for example, doesn't allow him to dismiss Hari’s personhood on account of her capability to feel pain, thus “the function of suffering is the same for Hari as it is for any human being–even though Hari is an alien with an entirely alien physical structure,” (Tumanov 369) is immune to harm and is capable of regenerating herself.

More importantly, in a Tarkovsky film, neither we nor the characters are ever given a final and full realization of the desire or ideal we are after. As Zizek notes, in Stalker, the condition of having your deepest desires made reality is that you are able to formulate those desires, which of course we're never able to do and why everybody fails once they reach the centre of the zone. Rather than giving us or his characters the satisfaction of a resolution or risking giving definitive answers to the questions that he puts forth, Tarkovsky reconciles to strobing us with what Zizek calls "religious obscurantism," through gestures of self-sacrifice. In Solaris, the closest thing that Tarkovsky gives us to an answer about whether or not Hari is human is a demonstration of her capacity for love, embodied in her self-sacrifice for Kelvin's well-being.

Via this gesture, rather than committing to a definition of what Hari is, Tarkovsky walks us through the progression and culmination of her internal process throughout the film. Solaris' ocean turns out to be a source, not of ghosts, but of love. It is love that moves Hari to sacrifice herself, love that restores Kris' humanity, and love that reveals to Kris, as Hyman puts it, "the validity of his father's humanistic—and socially divergent—viewpoint," (56). Love, portrayed in the film as "a dimension both cosmic and metaphysical" (56), accomplished by the sacrificial act of the extraterrestrial Hari, is what sends Kris back home, ego shattered, lesson learned, a prodigal son kneeling at his father's doorstep.

In this final scene, however, Tarkovsky finally pulls the rug from underneath our proposed understanding. We thought we saw humanity in action, we thought we understood the core logic of the film, embodied in Kris' words to Snaut that "Perhaps we are here to sense man as an object for love," We thought Tarkovsky was teaching us that love is the salvation of humankind, that sacrificial love was the highest of human pursuits, and that the limits of our humanity were determined by the limits of our capacity to love.

As Tarkovsky says in an interview, "Man is shaped by love. What does love mean? The ability to sacrifice, the ability to give oneself to other people,"

But in this final scene, as we ruminate on all that we've seen thus far, satisfied with this wholesome return home by our protagonist, before we are released from the film-scape by the movie's end credits, the camera pans away to reveal that this recreation of Rembrandt's Return of the Prodigal Son is happening, not on earth, but on an island on Solaris, and we are left wondering—was any of what we saw real? Was the father's home where the film began also the planet's creation? Were Kris or any of the scientists, let alone Hari, human in any sense?

THE PROBLEM OF DEFINITION

When it comes down to it, the greatest dilemma in this question for philosophers like Heidegger or Arendt, and the greatest opportunity for artists like Tarkovsky, is that there is no single answer to the question of what it means to be human, and the more I ask the question and search for the answer, the more I realize that I'm asking the wrong question, that I have even in fact missed Tarkovsky's point.

The question isn't whether or not Hari is human, nor what it means to be human, but rather, why, as humans, we are so predisposed to strip others of their personhood at the slightest chance.

The question, "Is Hari human?" is pertinent because of the diverse ways we see the scientists engage with her, and each of the three scientists represent a different inclination: to Kris, Hari becomes more human the more he spends time with her; to Snaut, Hari may not be human per se, but she is still a living creature worthy of respect; and to Sartorius, Hari is not only not human, but mechanical, to the degree that her existence forgoes any requirement of respect or otherwise.

To Sartorius, Hari is not human because a human has a specific biochemical composition that Hari does not share. Hari, to Sartorius, is a thing that, because of its composition from virtually indestructible neutrinos, and thus its ability to physically regenerate, he says it is more ethical to conduct experiments on her than on an animal.

What Sartorius overlooks in his assessment it Hari's awareness of herself and her surroundings, and has the ability to self-reflect, self-doubt, and self-harm. She has an awareness of her own "being-in-the-world" as Heidegger would call it, an awareness so overwhelming that she suffers from it. Arguably, Hari experiences enough emotional action in her short time on the station with Kelvin that she acquires a kind of ontological independence, and is capable of recognizing the danger and cruelty of Satorius' dehumanization of her and the other guests. Consider the library scene:

HARI: It seems to me that Kris Kelvin is more consistent than you. His behaviour is human in inhuman conditions while you act as if none of this had anything to do with you and consider your... guests... I think that’s how you call us... something external, disruptive. [...] I hate all of you!

SARTORIUS: What do you mean by that?! Please refrain from…

HARI: Please... don’t interrupt me. After all, I am a woman!

SARTORIUS: You are not a woman, neither are you human – can’t you understand that... if you are even capable of understanding anything at all. Hari does not exist. She is dead. And you... are just her iteration. A mechanical iteration. A copy. A matrix.

HARI [moving her hand across her tear-soaked face, breathing heavily]: Yes. Perhaps. But I am... becoming human. I feel no less than you do. Please believe me... I can manage without him. I love him. I am human. You... you are very cruel.

Her claim here, that "I feel no less than you do," demonstrates that while Hari may fail materially as a human, unable to perform structurally human tasks like drinking water or sleeping, being made of “unstable neutrinos” rather than being a carbon-based life-form, she is able to function conceptually like a human, to experience ontological suffering, to be a victim of her own thoughts and the abuse of others, to have awareness of being rejected and to experience the emotional pain of that rejection. She has love and anguish, she longs for closeness and connection, and what perhaps seals her status as a human, maybe even beyond human, is her self-sacrifice upon recognizing the suffering her presence brings to Kelvin.

Regardless, however, Sartorius never relents his need to "other". His “dismissal of Hari’s personhood and suffering…models analogous attitudes toward ‘the other’ within our own species” (Tumanov 373), and it is this attitude, this antithetical current to the love between Hari and Kris, that demands our attention and begs the question: what does "human" mean, and why has it become analogous with "worthy of respect"?

CONCLUSION

While our concern here has been the question of what it means to be human, in our inquiry, a question beneath the question reveals itself: why do we have the need, or even the ability, to make a distinction in the first place? As discussed, the term itself is a folk category rather than a term with scientific meaning.

When we look at how ordinary people have used the term “human” and its equivalents across cultures and throughout the span of history, we discover that often (maybe even typically) it is for the purpose of explicitly excluding members of our own species, such as when Yoav Gallant told the world last year that Israel was fighting human animals; or when the Nazis decided that there was only one "true" type of human, the Aryan; or when the fifteenth-century Spanish colonists made contact with indigenous inhabitants of the Caribbean islands and decided they were "savages"; or when the Portuguese decided that Africans were mindless heathens built for slave labor; and so on.

Sartorius, in a similar spirit, writes off Hari’s personhood, immediately stripping her of the capability of being human, or even of being perceived as human, given that she, like the other guests, is a non-biological structure, made of "unstable neutrinos". Tumanov relates the symbolic role of Snaut’s use of the concept of “stability” to the fact that “stability of character is what enables human bonding and personhood. We can establish emotional and other relationships with fellow humans only on the basis of certain behavioural predictability…essentially, this stability is what we mean by personality” (364). And while Hari does demonstrate a stability of character, a desire to bond, and a recognition of what it means to "be" stable, Sartorius has a need to “other” that hinges on whatever empirical evidence will allow him to do it with a clear conscience. His “dismissal of Hari’s personhood and suffering" Tumanov argues, "models analogous attitudes toward ‘the other’ within our own species” (373). On a psychospiritual level, Sartorius resists alchemical or personal development, and remains separated from any apparent return to his humanity, much like the settler colony resists integration with the way of the land it stumbles on. His moral deficit lends him a certain robotism that even Hari can recognize.

In discussing his intentions for Kris Kelvin, Tarkovsky tells us that "What was important to me was precisely that the human being unconsciously forces himself to be human, unconsciously and as far as his spiritual abilities would allow, he opposes the brutality, he opposes all that is inhuman while he remains human. And it turns out that despite him being - so it would seem - a thoroughly average guy, he stands at a high level spiritually. lt's as if he convicted himself, he went right inside this problem and he saw himself in a mirror" (Jerzy and Neuger 1985, 22).

So—is Hari human? Maybe, but perhaps that isn't the right question. Perhaps the question is: does Hari need to be human, or be perceived as human, to deserve respect? to be treated humanely? To Tarkovsky, we need forces like love, faith, and morality to ensure that people are treated humanely, and we are able to love, have faith in, and remain morally aligned with what reminds us of ourselves, what reflects us back to us.

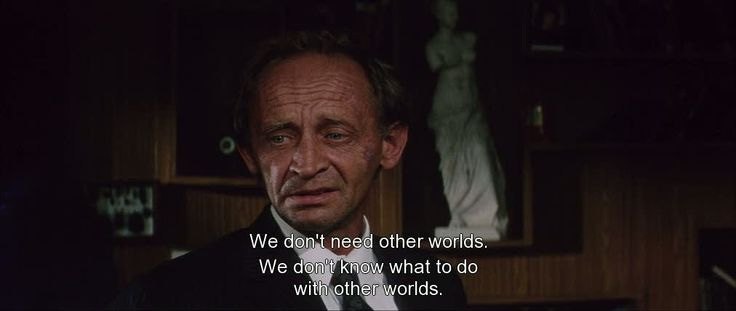

As Dr. Snaut puts it, "We don't need other worlds. We need a mirror. We struggle to make contact, but we'll never achieve it. We are in a ridiculous predicament of man pursuing a goal that he fears and that he really does not need. Man needs man!"

In Solaris, Tarkovsky offers us not a resolution but a labyrinth of ambiguities, a mirror reflecting back our most fundamental uncertainties about humanity. He leaves us with the unsettling but transformative task of reflection. Hari’s journey, and Kris’s reckoning, challenge us to abandon our preconceptions and embrace the fluidity of being. Humanity, Tarkovsky seems to suggest, is not a fixed category but a process—a striving toward love, sacrifice, and moral action. In the end, the question is not whether Hari is human but whether we, in recognizing her humanity, can become more human ourselves.

References:

"Andrei Tarkovsky: Art, Man, and the Meaning of Life" on The Excellence Reporter (2020). https://excellencereporter.com/2020/04/23/andrei-tarkovsky-art-man-and-the-meaning-of-life/

Arendt, H. The Freedom to be Free. 1964.

Heidegger, M. Being and Time. 1927.

Hyman, T. Review of Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky. Film Quarterly 29, 3 (1976): 54-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1211715

Kelly, D. "The guest: A-human ontology and Tarkovsky's Solaris". Science Fiction Film and Television 16 (2023): 5-31. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/901253

Szasz, T. The Second Sin. 1973.

Tumanov, V. "Philosophy of Mind and Body in Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris". Film-Philosophy 20 (2016): 357-375. DOI: 10.3366/film.2016.0020

Zizek, S. The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. 2006

Beautiful. To nurture one’s humanity through acting humanely towards oneself and towards all things. You have unlocked a new level of understanding and opportunity. Thank you for doing the work to mark the path and sharing it.

Love love love ✨👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽